We don’t stop playing because we grow old, we grow old because we stop playing

We don’t stop playing because we grow old, we grow old because we stop playing

(George Bernard Shaw)

"AGEING WELL"- THE CONNECTION TO MENTAL HEALTH

Written by our STAGE partners Odelia Ben Harush, R.N Ph.D, University of Haifa, with the contributions of Paola Buedo, MD PhD, Technical University of Munich

Mental health, as defined by the World Health Organization (WHO) is “a state of mental wellbeing that enables people to cope with the stresses of life, realise their abilities, learn well and work well, and contribute to their community” [1]. Also, mental health has been defined as the “enhancement of the capacity of individuals, families, groups or communities to strengthen or support positive emotional, cognitive and related experiences” [2] and the “subjective faculties enhance comprehensibility, manageability, and meaningfulness of a difficult situation” [3].

The definitions suggest that the absence of mental disorders alone is not sufficient to have good mental health; it is also necessary to improve people’s coping strategies, rather than simply trying to alleviate symptoms and deficits. Consequently, strategies to prevent mental disorders and to promote mental health are equally necessary, although they may overlap and complement each other [4].

Mental health is important at every stage of life. Unfortunately, one in every eight people worldwide lives with a mental illness, which is characterised by a clinically significant disturbance in cognition, emotional regulation, or behaviour. These illnesses are typically associated with distress or impairment in key areas of functioning [5]. Despite the significant burden of poor mental health, most people either do not seek, or significantly delay seeking, treatment [6].

World Mental Health Day, observed annually on the 10th of October, aims to spotlight mental health globally, raise awareness of mental health issues, and encourage efforts to support those experiencing these issues [7]. This day is an opportunity for all stakeholders working on mental health to discuss their work and highlight what more needs to be done to make mental health care a reality for people worldwide.

WHAT ARE THE CORE COMPONENTS OF MENTAL HEALTH?

Mental health can be divided into four components based on different theories and conceptualisations. The well-established four core components are cognitive health, emotional health, behavioural health, and social health [8]. These aspects of mental health are interrelated and are all crucial for overall wellbeing.

Cognitive health

Emotional health

Affective states that have arousing or motivational properties, leading individuals to specific responses or behaviours.

Behavioural health

Social health

Ageing and mental health

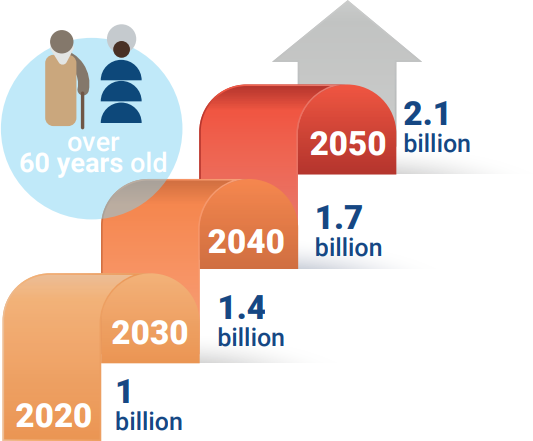

The world’s population is ageing rapidly. According to the UN, in 2020, 1 billion people were aged 60 years or older, a figure expected to rise to 1.4 billion by 2030, representing one in six people globally. By 2050, the number of people aged 60 years and older will have doubled to reach 2.1 billion, and the number of those aged 80 years or older is expected to triple to 426 million [9].

As the global population ages, there is growing interest in improving the quality of life. Promoting good mental health, especially in older age, is a crucial part of this endeavour. However, as people age, they may face life changes that impact their mental health, such as coping with a serious illness or the loss of a loved one. While many people adjust to these changes, some may experience persistent feelings of grief, social isolation, or loneliness, which can lead to mental illnesses like depression and anxiety.

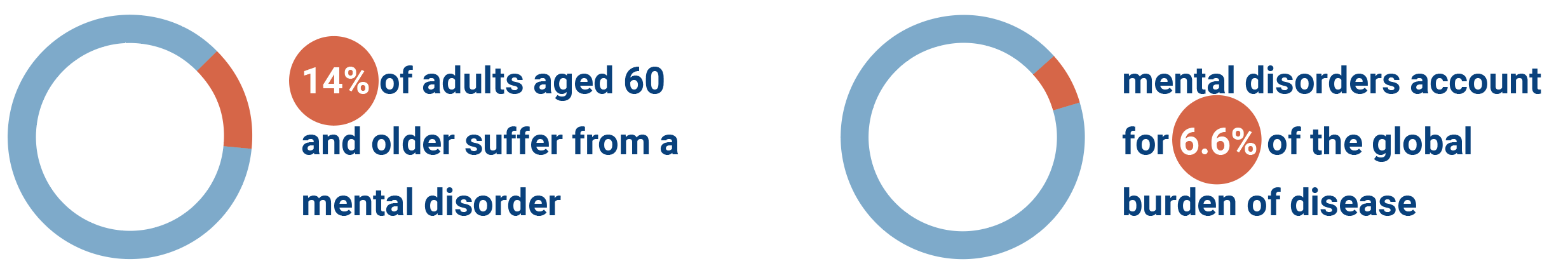

Data shows…[10].

Risk factors for poor mental health in later life

Certain drivers contribute to poor mental health, especially in later life. Here we describe some of them.

Social isolation and loneliness. Loneliness is a globally recognised risk factor, with detrimental impacts on the mental and physical health of older adults. Among older adults, social isolation is associated with a 20-40% higher risk of poor health and mortality, while loneliness increases the likelihood of mental health problems by 17% [12].

Physical health and multimorbidity. Long-term physical health conditions are more common among older adults than younger individuals and are associated with a twofold higher risk of poor mental health. There is also evidence that those with co-occurring mental health issues alongside physical illness have poorer outcomes for their physical condition, resulting in worse overall health [13].

Exposure to abuse. This includes any physical, verbal, psychological, sexual, or financial abuse, as well as neglect. One in six older adults experience abuse, often by their caregivers. Abuse has serious consequences and can lead to depression and anxiety [14].

Act as a caregiver. Many older people care for spouses with chronic health conditions, such as dementia. The responsibilities of caregiving can be overwhelming and may affect the caregiver’s mental health. Additionally, older caregivers often face the simultaneous challenge of managing their own healthcare needs [15].

Ageism and stigma. Ageism is defined by stereotypes, prejudice, and discrimination directed toward people based on their age.

Unfortunately, this negative view of later life may be internalised by older individuals and enacted, creating a vicious circle resulting in poor mental health. Ageism causes inequalities and has detrimental effects on the individual, community, and society [16] .

Lack of specialised staff. Older adults with severe mental illnesses may face unique challenges that are compounded by the ageing process. These challenges include managing the symptoms of their mental illness while also coping with age-related physical health decline, cognitive impairment, and social isolation, which can make treatment and care more complex. Elderly patients often take several medications along with psychiatric treatments, which can lead to polypharmacy, essentially, the use of “too many” medications. This raises the risk of drug-drug interactions, where one drug’s effect is altered by another, potentially reducing or enhancing effectiveness or causing unwanted side effects. The geriatric mental health workforce is understaffed, even in the most developed countries. Despite the increasing number of older adults, the number of psychiatrists trained in geriatric psychiatry has not increased [17].

stage

contribution

A common misconception is that older adults are a burden to society. In reality, many continue to work and contribute in various ways, such as through childcare, and running households. Most live independently, and many contribute several hours a week to volunteer activities or serve in leadership roles in community organisations ]18]. The concept of STAGE (Stay Healthy Through Ageing) reinforces this reality. Ageing with co-occurring physical and mental multi-morbidity is likely preventable and healthy ageing should be promoted to enjoy later life. STAGE aims to bridge the knowledge gaps needed to understand life-long processes, following a life-course approach, and their connections with biological, environmental, social, ethical, historical, and infrastructural factors.

Conclusion

World Mental Health Day serves as a vital reminder of the need to prioritise mental health across all ages, especially in our ageing population, and with a promotional approach to the strengthening of our mental health together with the prevention of mental illness. The STAGE concept emphasises the importance of understanding and addressing the interconnected factors contributing to healthy ageing. By promoting mental health and preventing multi-morbidity, we can improve the quality of life for older adults, allowing them to continue their meaningful contribution to society.

As we strive to add healthy years to life, let us not forget to add life to those years by nurturing the mental well-being that allows our elders to flourish, not merely survive.

Glossary

Drug-drug interaction: A change in a drug’s effect on the body when the drug is taken together with a second drug. A drug-drug interaction can delay, decrease, or enhance the absorption of either drug. This can reduce or increase the action of either or both drugs or cause adverse effects.

Polypharmacy: ‘Too many’ drugs instead of a simple numerical count of medications, which is of limited value in practice. The exact number of drugs changes according to the different definitions.

References

[1] World Health Organization. (2001). Strengthening mental health promotion. Fact sheet, 20.

[2] Hodgson, R., Abbasi, T., & Clarkson, J. (1996). Effective mental health promotion: a literature review. Health Education Journal, 55(1), 55-74.

[3] Huber, M., Knottnerus, J. A., Green, L., Van Der Horst, H., Jadad, A. R., Kromhout, D., … & Smid, H. (2011). How should we define health? BMJ, 343.

[4] World Health Organization. (2004). Promoting mental health: Concepts, emerging evidence, practice: Summary report. World Health Organization.

[5] Mental Health Atlas 2020. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2021

[6] “The State of Mental Health in America”. Mental Health America. Retrieved 2024-02-27

[7] Jenkins, Rachel; Lynne Friedli; Andrew McCulloch; Camilla Parker (2002). Developing a National Mental Health Policy. Psychology Press. p. 65. ISBN 978-1-84169-295-1.

[8] Fusar-Poli, P., de Pablo, G. S., De Micheli, A., Nieman, D. H., Correll, C. U., Kessing, L. V., … & van Amelsvoort, T. (2020). What is good mental health? A scoping review. European Neuropsychopharmacology, 31, 33-46.

[9] World Population Prospect 2022: release note about major differences in total population estimates for mid-2021 between 2019 and 2022 revisions. New York: United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division;2022.

[10] Institute of Health Metrics and Evaluation. Global Health Data Exchange (GHDx).

[11] World Health Organization. (2001). The World Health Report 2001: Mental health: new understanding, new hope.

[12] Hong Teo R, Hui Cheng W, Jie Cheng L, Lau Y, Tiang Lau S. Global prevalence of social isolation among community-dwelling older adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2023 Apr;107:104904.

[13] Halstead, S., Cao, C., Mohr, G. H., Ebdrup, B. H., Pillinger, T., McCutcheon, R. A., … & Warren, N. (2024). Prevalence of multimorbidity in people with and without severe mental illness: a systematic review and meta-analysis. The Lancet Psychiatry, 11(6), 431-442.

[14] Yunus, R. M., Hairi, N. N., & Choo, W. Y. (2019). Consequences of elder abuse and neglect: A systematic review of observational studies. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse, 20(2), 197-213.

[15] Talley, R. C., & Crews, J. E. (2007). Framing the public health of caregiving. American journal of public health, 97(2), 224-228.

[16] Nelson, T. D. (2016). Promoting healthy aging by confronting ageism. American Psychologist, 71(4), 276.

[17] Mendonca, C., & Kyomen, H. (2023). Addressing the Geriatric Psychiatry Workforce Shortage: Can Geriatric Psychiatry “Mini-Fellowships” Be Part of the Solution? The American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 31(3), S81-S82.

[18] Reynolds 3rd, C. F., Jeste, D. V., Sachdev, P. S., & Blazer, D. G. (2022). Mental health care for older adults: recent advances and new directions in clinical practice and research. World Psychiatry, 21(3).